Agribusiness and Trade: Drones transform NZ farms from above

- Drone use is growing in NZ, with around 60 members now in the Agricultural Drone Association.

- Drones fill a practical niche between ground-based equipment and helicopters.

- The association is working with the Civil Aviation Authority to improve the certification process.

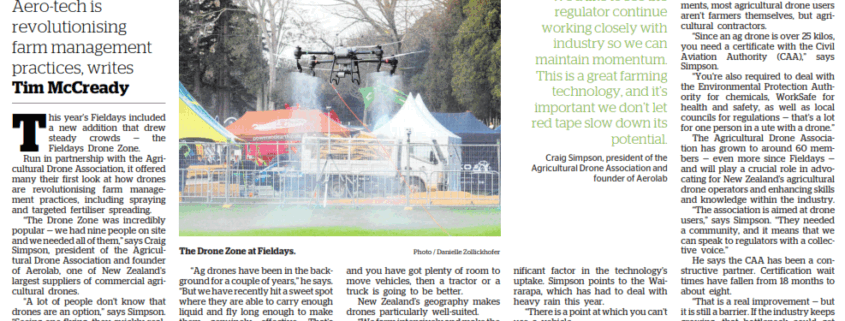

This year’s Fieldays included a new addition that drew steady crowds – the Fieldays Drone Zone. Run in partnership with the Agricultural Drone Association, it offered many their first look at how drones are revolutionising farm management practices, including spraying and targeted fertiliser spreading.

“The Drone Zone was incredibly popular – we had nine people on site and we needed all of them,” says Craig Simpson, president of the Agricultural Drone Association and founder of Aerolab, New Zealand’s largest supplier of commercial agricultural drones.

“A lot of people don’t know that drones are an option,” says Simpson. “Seeing one flying, they quickly realise they are big machines that can carry a significant spray pack, and gain a better understanding of how they work.”

The use of drones is reshaping how work gets done on New Zealand farms, with significant growth over the last few years. There are now hundreds of large agricultural drones operating across the country – up from around 20 or 30 three years ago. Simpson says Aerolab’s sales have doubled in the past year alone.

“Ag drones have been in the background for a couple of years,” he says. “But we have recently hit a sweet spot where they are able to carry enough liquid and fly long enough to make them genuinely effective. That’s when the market really took off.”

Drones fill a practical niche between ground-based equipment and helicopters, and their rise is changing how agricultural contractors operate. They can open up access to land that might previously have been too steep or too wet for traditional agricultural machinery, or that require immediate attention and more precision.

“If you’ve got 100 hectares to do, a helicopter is always going to be the best choice,” he says. “And if you’ve got lots of ground, it is dry, not steep, and you have got plenty of room to move vehicles, then a tractor or a truck is going to be better.

New Zealand’s geography makes drones particularly well-suited.

“We farm intensively and make the most out of small holdings,” says Simpson. “We’ve got a lot of arable land but not a huge amount of it is flat. Even with beef and sheep, we run stock on quite steep country. A drone is a real nice fit.”

This is opening up new possibilities. “Some farmers never dealt with gorse on steep blocks because the only option was spraying with a backpack. A helicopter wasn’t economical. Now a drone contractor can do the job at a reasonable rate.”

Urgency has also become a significant factor in the technology’s uptake. Simpson points to Wairarapa, which has had to deal with heavy rain this year.

“There is a point at which you can’t use a vehicle. In the past you might ring a helicopter provider and be told there is a four-week wait. Meanwhile, the fungus gets a foothold.

“A drone provider might be the same price, but they can be there the next day. You can deal with the problem faster and ultimately use less chemicals.”

Safety is another driver of demand.

“Why drive a quad bike or a vehicle across a steep hillside when you can instead fly over it with a drone and keep everyone safe?” says Simpson.

Given the compliance requirements, most agricultural drone users aren’t farmers themselves, but agricultural contractors.

“Since an ag drone is over 25 kilos, you need a certificate with the Civil Aviation Authority (CAA),” says Simpson. “You’re also required to deal with the Environmental Protection Authority for chemicals, WorkSafe for health and safety, as well as local councils for regulations – that’s a lot for one person in a ute with a drone.”

The Agricultural Drone Association has grown to around 60 members – even more since Fieldays – and will play a crucial role in advocating for New Zealand’s agricultural drone operators and enhancing skills and knowledge within the industry.

“The association is aimed at drone users,” says Simpson. “They needed a community, and it means that we can speak to regulators with a collective voice.”

He says the CAA has been a constructive partner. Certification wait times have fallen from 18 months to about eight.

“That is a real improvement – but it is still a barrier. If the industry keeps growing, that bottleneck could get worse.

“We’d like to see the regulator continue working closely with industry so we can maintain momentum. This is a great farming technology, and it’s important we don’t let red tape slow down its potential.”

Simpson says that with their speed, precision, and ability to tackle challenging terrain, agricultural drones are on their way to becoming a familiar sight on New Zealand farms – not just a novelty attraction at Fieldays.